Summer camp, then and now (via

NewsWorks)

July 2, 2013 By Jonathan Zimmerman Download Audio File » Listen to the interview. (Reposted with permission from www.newsworks.org)

I went to three different summer camps when I was a kid, in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I swam, hiked, and played sports (badly). And sometimes, I did nothing at all. That's what summer — and camp — were all about.

My, how times have changed.

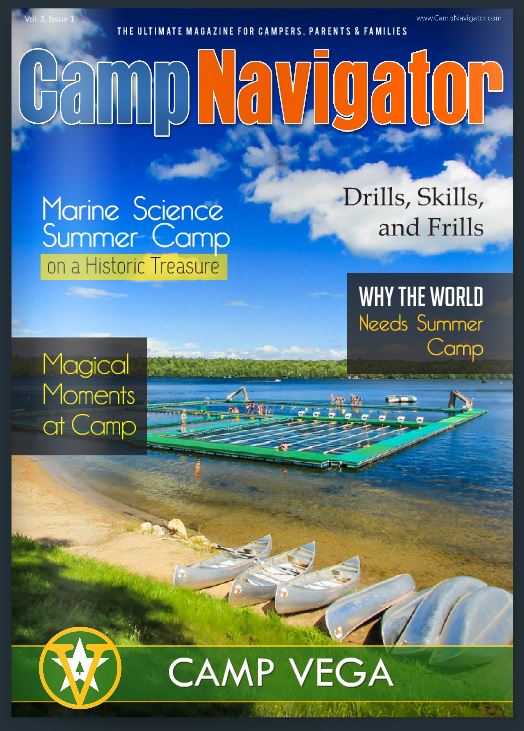

About 20 years ago, so-called "specialty camps" began to replace the general-interest kind that I attended. So now you can go to camps that stress particular activities, from cooking and computers to robotics and rocketry.

Even at general-interest camps, meanwhile, kids are much more likely to receive professional athletic coaching, top-of-the-line art and music instruction, or even SAT-prep classes. Camp isn't just for fun anymore. It's about building a resume, a skill-set, a profile, a future. Like school, camp now prepares young people to win the great Race of Life. And that's a big loss, for all of us.

Camps more like school now

Ironically, summer camps began as an antidote to school rather than an extension of it. According to Ernest Balch, who founded the country's first camp in 1881, formal educational institutions were making young men "soft." Boys needed a rugged outdoor experience to escape the "weakening feminine influences" of modern society.

Around the turn of the century, the YMCA and the Boy Scouts started summer camps. So did groups with names like the Woodcraft Indians and the Sons of Daniel Boone, all devoted to recovering the lost rustic masculinity of the old frontier.

In 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner had famously described the frontier as the key to American identity. In the same essay, however, Turner announced that the frontier was gone! So summer camps would keep its spirit alive. With their simple tents and cabins, camps would give boys "the sturdier training of our forebears," as one camp advocate wrote.

Girls' camps arose, too, so that young women from the city could breathe fresh country air and grow into healthy mothers.

"The old-time education of girls kept them too much under cover," a Girl Scout magazine warned in 1917, "too much confined to books, too little free to engage in sports that might spoil their clothes."

Camp would free both sexes from the stifling effects of over-civilization, even as it reinforced their separate roles.

Naming roots

To do that, camps borrowed names and activities from the "primitives" who preceded whites on the frontier: Native Americans.

Indian-style ritual "gives the boy the much needed opportunity to express his inherent savagery," one camp brochure declared. "Just to be free, to run, to climb, to shout and yell like a wild Indian on a war-path!"

Girls, meanwhile, made Indian skirts and jewelry. And several camps boasted that they hired actual Indians, rendering the camps more "authentic" than their competitors.

Eventually, this same competition would lead many camps to forsake their simple facilities on behalf of modern amenities, especially electricity and indoor plumbing.

"Will they come back to your camp?" asked an advertisement for flush toilets in a 1931 camping magazine. "The parents — who pay the bills — must be satisfied that your camp is absolutely sanitary."

Many camps also began to show Hollywood movies at night, tapping into young people's growing appetite for commercial culture. But others balked at it, holding the line against "the tidal wave of jazz and crowded hall and movie and cabaret," as one director wrote.

Pop-culture restrictions

Into the present, some camps still try to insulate kids from popular culture by barring smartphones and blocking the Internet. But they're fighting a losing battle. Camps now offer film-making, Web design, and "field trips" to amusement parks and malls. And many of their activities — like cooking competitions — are ripped straight from reality TV.

Most of all, though, camps advertise skills that will allegedly help kids succeed in the so-called real world. By the 1990s, the rising cost of college — and the increased competition for admission — made families ever-more anxious about their children's future. Why waste a summer at a general-interest camp, when you could be gaining "aptitudes" and "experiences" that will separate you from the pack?

That seems like a great way to deny kids their childhood. There will be plenty of time, later in life, to plot and strategize about moving up in the world. Trust me, I'm an adult. I do that all the time.

But when I was a kid, I didn't.

The last camp I attended proclaimed itself "the camp with the pioneer spirit." That meant sleeping outside, running around barefoot, and, yes, participating in "Indian" ceremonies. You developed important life skills--including cooperation and compromise — but you didn't have to stand out from the tribe. It was about getting along, not getting ahead.

And I'll always be grateful for that.

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches education and history at New York University. He is the author of "Small Wonder: The Little Red Schoolhouse in History and Memory" (Yale University Press).

.jpg)

.jpg)

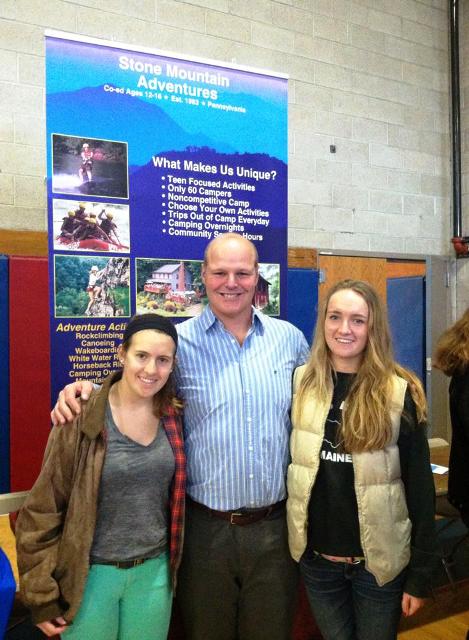

with THON for the past three years while a student at Penn State University. The PSU Dance Marathon, commonly referred to as THON is:

with THON for the past three years while a student at Penn State University. The PSU Dance Marathon, commonly referred to as THON is:.jpg)

.png)